“So, having solved this one set of things, but without making fundamental shifts in how we ran the world, we were setting ourselves up for much deeper trouble.” Bill McKibben, The Last Archive (podcast), 2022

There is a Slow Lane ring to how environmental activist Bill McKibben describes one of the biggest challenges of our time. We have, in other words, come to the end of the line of our quick fixes. Those convenient or technical hacks that create visible results and buy us just a little more time (and hope), before we have to face up to the reality: What is broken can’t be plastered over no more.

“And the problem is that the things that we're addressing are the easy things, it turns out. They're the problems, that when something goes a little wrong, like you don't have the right filter on your smoke stack, or your car or whatever, and you can fix them by putting a catalytic converter in or a scrubber in your smokestack, and yeah, it costs a little money, but it's not the end of the world. And once you do that, you've made extraordinary progress.”

How the United States responded to environmental issues became a textbook example of how the Fast Lane tackles problems by getting quick wins. McKibben describes how, in the 1970s, there was a window of opportunity: Jimmy Carter, then president, opened it by announcing an all out commitment to solar power to gain energy independence from imported oil. Predictably in a polarized two-party democracy, President Ronald Reagan, who defeated Carter in the 1980 elections, closed it by leaning into fossil fuels. As a result, the United States lost more than three decades stuck in a petrol economy that kept warming up the planet, before getting serious about renewables.

The Insult Of Servicing The Problems

It was just one missed opportunity, out of many. Every homeless shelter we build is a manifestation of society not trying to end homelessness, but accommodating the problem. Taking the eyesore off our streets, but not ending the suffering of those affected. Every sheltered workshop, a place where people with disabilities are employed separate from others and exempted from regular labor standards like minimum wages, is an active manifestation of not including everyone in society or the economy. Again, the issue is tucked away out of sight at the hefty price of destroying the lives of people denied the dignity and independence that comes with inclusion in the real economy. The same applies to countless other quick fixes that do nothing but treat the symptom, not its cause. Like using Band-Aids to treat cancer.

Ah, So That's What It's For!

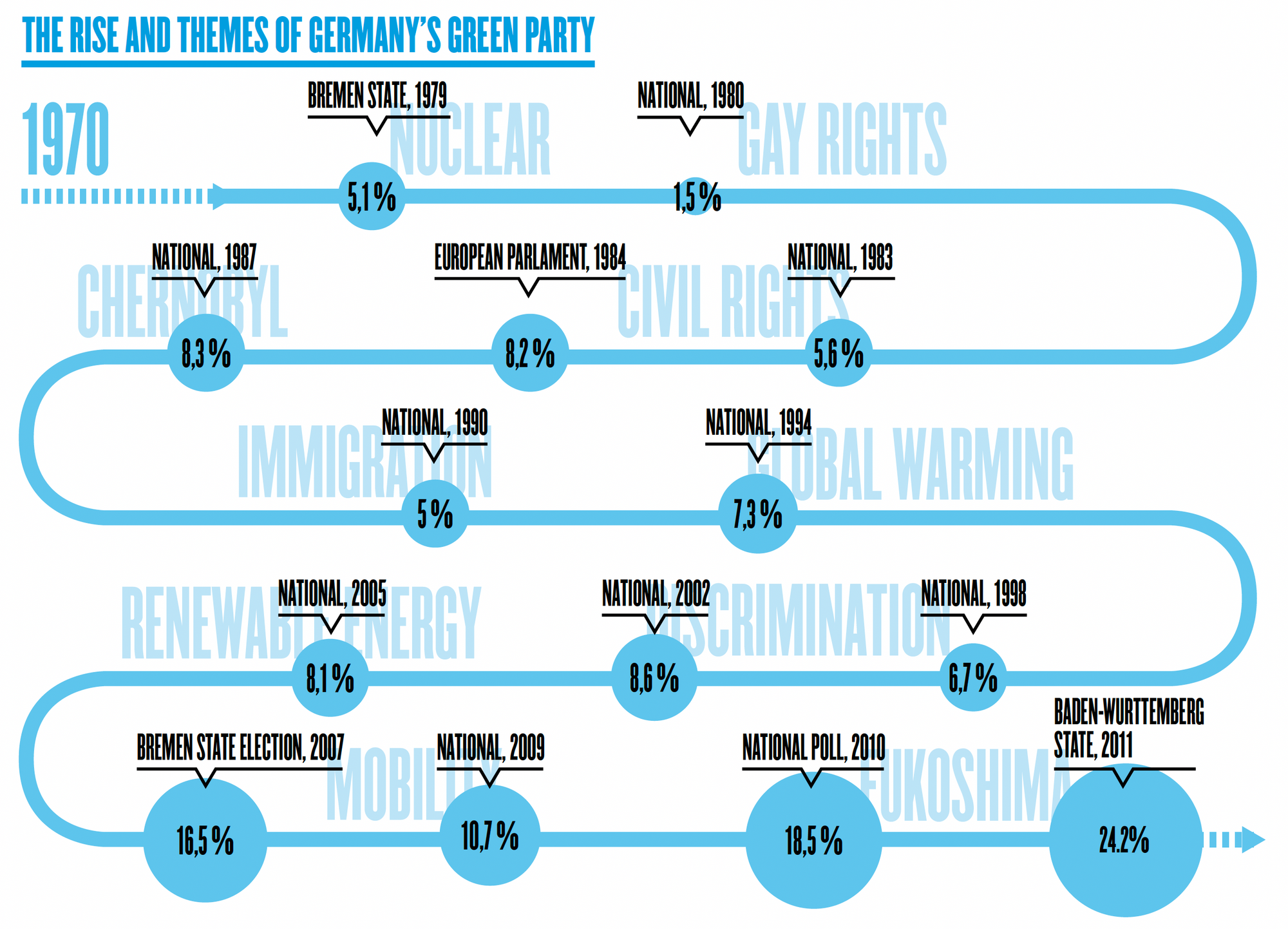

What makes the Slow Lane so counter-intuitive, is that it often builds an infrastructure that, at first glance, appears to be too participatory for the quick fixes. After all, you don't need a green political party to install air filters or mandate clean rivers. The environmental movement in the United States never sparked a political party like the Green Party in Germany, but instead focused on using institutions to create laws and lawsuits to get quick results. But in Germany, the Green Party today is a major political force, an equal to the traditional two big parties. Now imagine a world, where there were three, not two, viable parties with a real shot at winning elections to choose from in the United States. And further, what if that third party was designed, like the Green Party in Germany, not just to pursue environmental causes, but also played by different, more transparent and democratic rules?

It wasn't the focus on quick wins like air filters that stopped this from happening in the United States, after all, Germany did those, too. And building a Green Party was no easy feat. In Germany, the environmental movement simply felt a political party was needed to achieve more. It wasn't a quick win. In the 1970s and 80s, the party won just over 5% in a few local and state elections. It only gained real traction following the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986. And it was a party that was playing by new rules, to accommodate numerous groups that completely distrusted one another: environmentalists, landscape conservationists, conservative farmers, families, leftist activists.

Readying Democracy

Lacking billionaire funders who were willing to throw big money at the cause, like in the United States, activists thought that alliances were needed to achieve real results. At times, they succeeded, but in truth, Germany has a mixed environmental record thanks to intense industry lobbying. The real, undisputable outcome was that this way of organizing, less transactional and more structural, reformed and energized a tired two-party political system. A win for democracy! It produced a major piece of democratic infrastructure that represented a new generation of ideas and causes, and made Germany more prepared to meet the much deeper, interconnected challenges of a warming planet. After forty years, the Slow Lane had gotten the country into the starting blocks for something much bigger.

In my reading, in the long game of real change, that's the kind of fundamental shift that Bill McKibben referred to. And it may turn out to be a bigger win than Jimmy Carter's solar panels.