Let's explore the rich and complex relationship of data and technology with the Slow Lane. The question is how data and technology can live up to their promise, when we have to deal with complex human needs.

"The biggest critique that Freefrom gets, almost always from people in the tech world, is that we're doing too much. We've gotten a lot of pushback that we aren't using technology across the board." - Sonya Passi, Founder of Freefrom

Why of all things would people from the tech world criticize Freefrom, a non-profit organization that ensures that survivors of intimate partner violence have the resources to get safe, heal, and prevent future harm?

The answer goes right to the heart of the love/hate relationship between the Slow Lane and tech.

The Promised Land

Serlo is the kind of success story that gets the Slow Lane excited about the promises of technology. A group of high school students who built their own collaborative learning platform, inspired by Wikipedia. Serlo is tailored to empower students with diverse learning needs, and despite its miniscule EUR 350,000 budget, it serves 1,5 million students every month. Technology, here, makes it possible to serve countless students for free without commercializing their data. Technology, here, spreads the tools for great education experiences, powered by students, teachers, and volunteers. As an organization, Serlo is owned by members of a non-profit association – teachers, students, contributors – all committed to keeping Serlo free, and free from advertising or other commercial practices. It is transparent about where its money comes from. Decisions aren't taken by executives, but a plenary of forty-five members of the team. The whole of Serlo, in short, is simply designed to empower young people to learn better, individually and in teams.

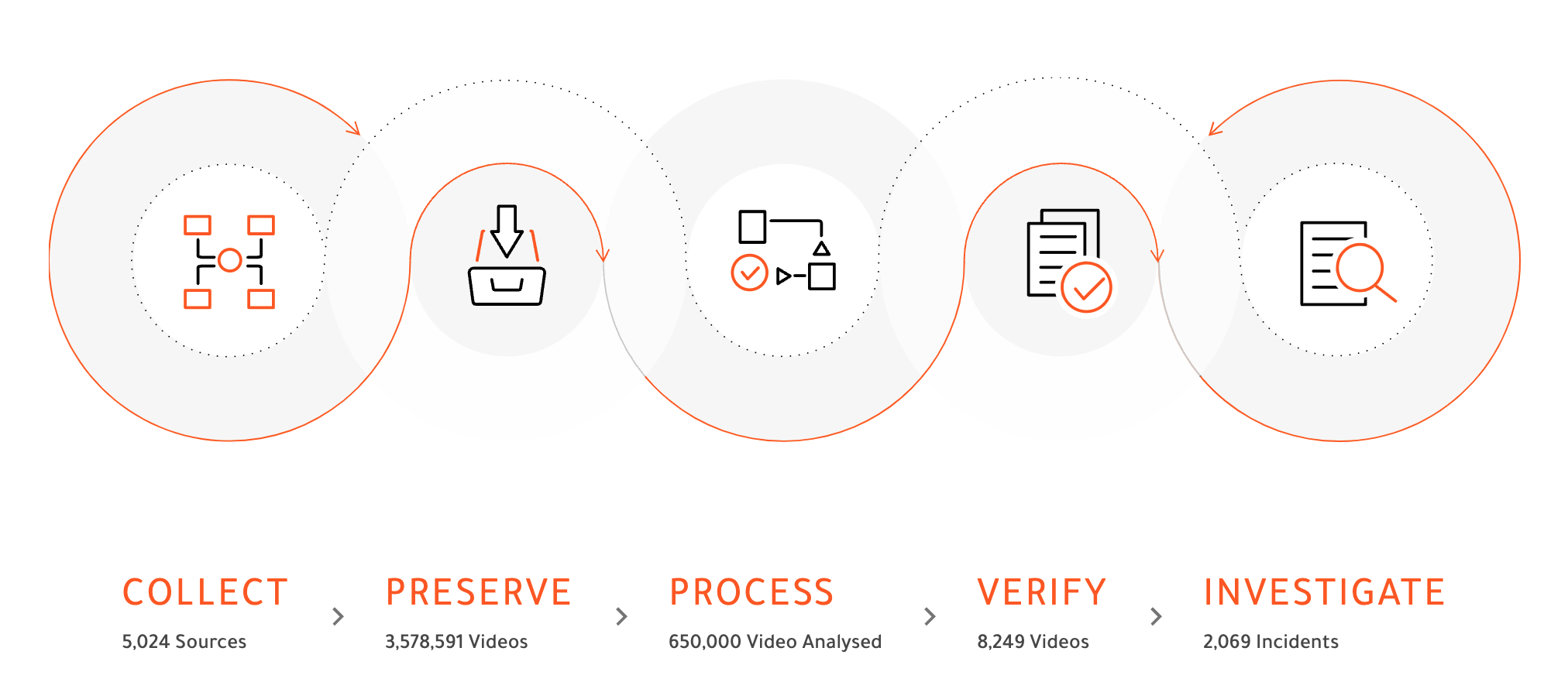

Building a piece of technology that is useful to an almost unlimited number of users is a compelling proposition. Movements hope to achieve the kind of network effects that have made Serlo so cost-effective, in which users become volunteers who create more content, that, in turn, makes Serlo more useful to students and teachers. And like Community Solutions, many Slow Lane movements are interested in data to improve their outcomes. Built for Zero collects real-time, by name data to more effectively help every person experiencing homelessness (see Story). In other cases, movements collect data. The Syrian Archive collects thousands of videos of human rights violations uploaded by people in Syria. It is run by Mnemonic, an NGO that provides this data openly, to support the work of human rights defenders, like journalists and investigators. Without it, human rights organization risk losing vital evidence to the moderation practices of platforms like Facebook or YouTube.

If Only It Wasn't So Hard

"We have laws that work against us solving intimate partner violence. I can't create an app to fix that. I've got to engage with the humans. Part of the way that intimate partner violence thrives is that it isolates people. And it creates such financial devastation, that you're unable to engage in your community and your society in a way that you once could or would want to. I can't create an app for breaking isolation, either." - Sonya Passi

Tech holds all these promises, and more. Making it happen, is much harder. And that brings us back to Sonya Passi's comments, about her biggest critics being people from the tech world. Most of the money to fund the costly, and risky, development of technology comes from people who have made it in the tech business. Few Slow Lane movements have the skills that Serlo had, to build their own technology. Technology is so costly to develop, in part because programmers are expensive, but also because it is so hard to build something that works. It takes a lot of trial and error to see, for example, if students will use a learning tool. Then, it can take a very long time to get a lot of users to achieve the desired impact. Technology only really becomes cheap once it is successful. Conventional donors and philanthropists have long preferred to fund predictable projects that are guaranteed to help people. That changed, when successful tech entrepreneurs looked to bring their experience to the field of social change. They provided a new opportunity to the Slow Lane, enthusiasm and money for tech.

Go All In!

We can work backwards from here. People from the tech world criticized Sonya because they wanted her to reach more victims, faster. Their instinct was to do what they had done in business: get to scale, fast. Instead of offering a variety of services to survivors of intimate partner violence, they wanted her to pick one service, like providing money, and use technology to make it big. Sonya insisted that this made no sense, when complex human conditions call for holistic care, not a quick fix. Sonya was also interested in developing technology to become more effective and empower more people. Many people from the tech world lose interest at this point. Tech for them is an all or nothing game.

Here is how investors explained this 'all in' logic to me. Tech is incredibly risky, so hard to get right. Unless your organization is 'all in', it will not be committed enough to make it work. The result, a half-baked solution that is at best assistive, instead of transformative. Another way to ensure success in tech is the team. Great people deliver really great results, whilst average teams are likely to fail. Great tech people aren't interested in working on the sideline of an organization that also values other things. They want to be in an all out tech organization. This logic is deeply ingrained in the sector, especially among people who have succeeded in the tech business.

Most of the money to fund the costly, and risky, development of technology comes from people who have made it in the tech business. A conversation about tech with them, can quickly turn into an all or nothing bet.

The Truism

But is 'all in' true, or a self-fulfilling prophecy? It is true, that most organizations who 'also built an app', ended up not really transforming the world through their technology, nor maximize its potential. More inclined to play things safe, they may stop investing when things don't work. The truism here is, that tech funders will not fund projects that are not 'all in', meaning that their money and expertise is simply not available to other projects. Without their commitment, projects end up with less money to get it right. And too many good coders have bought into the same narrative, repeated everywhere, and remain uninterested unless the project is 'all in'. What they fail to see is how Fast Lane success is not in fact a model for technology to improve society. Sonya doesn't want to pick a problem that technology can solve, or grab market share, or 'lock-in' survivors of abuse. She wants to empower survivors of abuse, whatever that takes.

Success stories like Serlo cannot easily be translated to the wider Slow Lane. They work because they solve a problem that tech can solve in the first place. Serlo also benefits from the school environment, where teachers create a learning environment around their technology. The same doesn't hold true for Albina Ruiz's movement to empower waste-pickers in Peru. Tech could have helped her movement organize, or even track the implementation of laws more efficiently. But the all-in question would have had disastrous effects. Betting scarce resources on an app would have never worked and might have destroyed the whole movement. Albina would have seen it as a distraction from the actual work of empowerment. Rosanne Haggerty once told me, that every so often a Mayor or city manager will get seduced by a startup pitch that promises to solve homelessness. It is a distraction, setting back serious reform efforts to do what actually works.

The real question is how technology and data can live up to their promise, when we have to deal with complex human needs.

A New Playbook

Until recently, there were really only two playbooks to succeed in technology. One was the open-source movement playbook, that at times brought thousands of volunteer contributors together to build an ambitious project, like Wikipedia, Linux, Firefox, or Serlo. The other is the startup playbook, in which a small team takes the risk to create a technology that generates enough excitement to grab and control a market. Along the way, venture capital investors place bets on their success. The startup playbook has famously given us the stars of the Fast Lane like Facebook, Uber, Amazon, and Tesla. With all their negative externalities when it comes to privacy, surveillance, data hoarding, manipulation. What both playbooks have in common, despite their different purposes, is that they are both 'all in', and that they rely on people who believe in technology as a solution, and want to focus on problems that technology can solve. Predictably, the people in charge of these projects lack diversity. Even Wikipedia suffers from this homogeneity, attracting far fewer female contributors than men.

Neither playbook responds to the needs of the Slow Lane, where complex human often defy tech fixes. Other, promising ideas have emerged. They come with names like Public Interest Technology, Civic Tech, and Societal Platforms. What they have in common is a deep commitment to solving not just for the majority, but solving for everyone. And seek to rectify many of the concerns about Fast Lane technologies.

What successful tech entrepreneurs fail to see is how Fast Lane success is not in fact a model for technology to improve society.

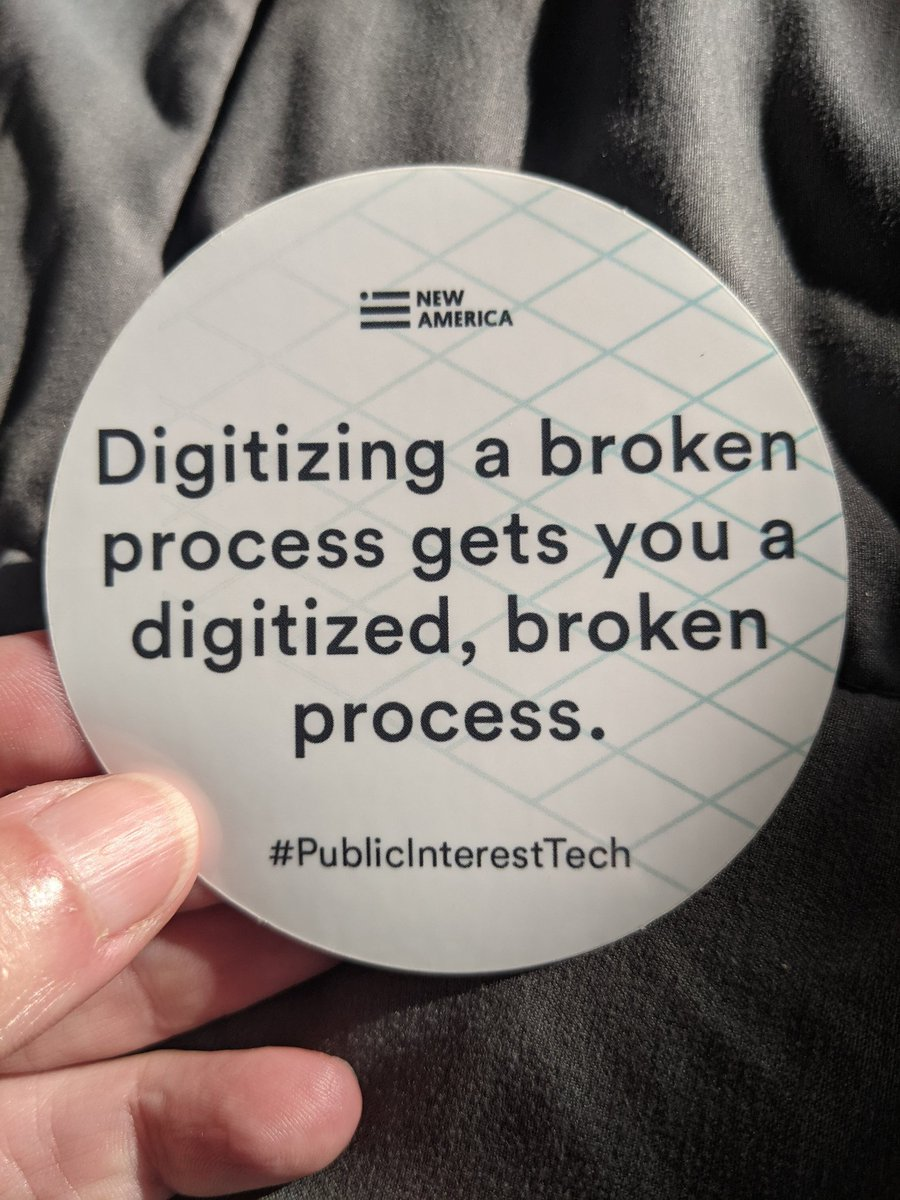

Public Interest Technology, for example, has become a new method to rebuild online services, like benefits or food stamps, delivered by governments and public agencies. Here, teams put people first, involving them to replace overly complex corporate systems with simpler services, designed to the needs of users. Technology here is only a part of what makes a public service successful. In the words of my former colleague Hana Schank, of New America, “Digitizing a broken process gets you a digitized, broken process”. Civic Tech caters more to the needs of political and social activists, building tools to organize movements or campaigns, or offering direct services to underserved people. Societal Platforms are a more recent development, and have emerged from a movement that promotes 'digital public goods'. The idea of digital public goods is to build a trusted alternative to the dominant platforms like Facebook or Amazon, or intrusive government systems. It is the most comprehensive of all playbooks, looking to create truly open systems that serve the public. Societal Platforms are open to anyone, as user or contributor, to enable the kind of positive network effects that make Serlo possible.

Slow Lane Technology?

Taken together, these movements represent a mindset shift about the role of technology should play in social change. They also offer a new resource. This crowd is more diverse than the traditional startup and open-source communities were. And it offers a broader skill-set to understand and solve for human needs. What is emerging is a new community of practice that is not insisting that everyone has to be 'all in', but is delighted to contribute in environments that deal with complex human needs can co-exist with technology.

In early 2020, my colleague Karen Bannan at New America and I hosted a webinar to explore how we can deal with technology in the Slow Lane, when technology isn't the only answer. We invited Sonya Passi and Eric Dawson, the founder of Peacefirst because both of them work with complex needs of people, and are hopeful about technology. We found that technology is never neutral, but deeply intertwined with the Fast Lane dynamics of power and domination.

The solution? Everyone needs to take a lesson in humility.

"The Slow Lane is being rooted in humility. And humility to me is not about lowering yourself, it's about how do we create space for other voices and draw the circle bigger with our muscles and our love." - Eric Dawson, founder of Peacefirst