This week, we continue our investigation of scale by following Rosanne Haggerty's journey from building supportive homes in New York City to a successful national movement to eliminate homelessness in a hundred American cities. Less known to people following her work on eliminating homelessness, is her organization's experiment with community organizing. For over a decade, her organization has patiently supported the people of Brownsville, New York City, to develop their own bold practice of social imagination. Along the way, they have mastered sophisticated data-practices to transform the early childhood experience in their community.

Built With Beauty for 416

As I walked up to the Prince George Hotel, it was stunning. Absolutely stunning. Tucked away to the side of Times Square in Manhattan, the grand building was full of stories and mysteries. Walking in, I noticed the kind of all-glass security gates I had seen in fancy office buildings. But as I waited to observe the people coming and going, I noticed that this was no fancy office, hotel, or apartment building. The Prince George Hotel offers supported living to formerly homeless or low-income individuals. Half of the tenants live with HIV/AIDS, a mental illness and/or a history of substance abuse.

I first came here in 2012, to meet Rosanne Haggerty. She was one of the driving forces behind the Prince George, buying it in 1995 with Common Ground, a non-profit she co-founded in 1990. The loving restoration was no indulgence. Design is one of Rosanne’s many secret weapons. She believes places shape people and vice-versa. As if to underline this point, her own office was austere, simple. It reflects a sense of mission and personal responsibility to do something about poverty and loneliness that had already defined her life.

It was a seven-year-long, $48 million journey to turn around a former hotel that had declined into an overcrowded and dysfunctional homeless shelter, housing 1,700 people in the 1980s. It was a gigantic lift for Rosanne and her team to raise the necessary funding. New York City provided half the funding through long term low-interest loans, the other half came from the sale of historic preservation tax credits—a model which allows for the actual sale of tax advantages, and corporate bridge-financing by banks. When “The Prince George re-opened in 2002, it was the overwhelming beauty and detail that surprised visitors most. It is part of a plan to give dignity to people who are commonly stigmatized. And it provides income: the beautifully restored “Prince George Ballroom” is also a premium venue for events.

But to succeed, The Prince George needed to be beyond beautiful: Rosanne teamed up with organizations to provide the whole package of activities to help people re-enter society: case management, training, crafts and art spaces, healthcare, job support, and social care services. Each partner brought unique capabilities, but also funding models that helped sustain the entire operation.

The idea behind the Prince George is as simple as it is effective. Give people a stable, safe and supportive home, and they can focus on important things like finding a job. Community programs have helped involve locals in the neighborhood to help the 416 residents of the Prince George Hotel succeed in life. After the Prince George, Rosanne and Common Ground went on to convert or build more than 3,200 supported affordable housing units in the States of New York and neighboring Connecticut, like those provided by the Prince George Hotel.

Built With Truth for 100,000

In 2011, following her work with Common Ground, Rosanne launched a new organization, Community Solutions. Initially, the goal was to build 100,000 homes in America (which they did). Despite its success, none of the participating cities ended homelessness. Rosanne and her team identified four underlying issues holding back progress. First, no one was responsible for ending homelessness. Second, people who fund progress only measure the success of their specific investment, not the overall impact on reducing homelessness. Third, data was poor. It was collected only once a year, wasn't accurate, and left out key information. And fourth, the housing system was broken, as newly built stock didn’t deliver outcomes on reducing homelessness.

It turned out that cities had a margin of error of around 240% when counting the homeless. A Mayor might think they have 2,000 homeless, but the number could be as high as 6,800 or as low as 700.

Rosanne and her team began to look for ways to not just serve homeless people, but try to reduce homelessness. In 2015, they launched a new, ambitious campaign: “Built for Zero” – to end homelessness in American cities. It turned out that cities had a margin of error of around 240% when counting the homeless. A Mayor might think they have 2,000 homeless, but the number could be as high as 6,800 or as low as 700. Why is the number so hard to get? Because cities only count once a year, sending teams out on a single day for 24 hours to find them. The resulting number is unreliable, and doesn’t tell city officials what to do, what these people need. A generic measure, it leads them they offer generic help, not responding to the actual needs of people. Rosanne experienced first experienced this in 1982, when she worked in a homeless shelter. The shelter offered beds, but what people actually needed was help with finding a job and finding a home.

What cities actually require to tackle homelessness, is what Rosanne calls “realtime, by name” data on every homeless person. Because once you have that, you can actually solve the problem.

Ending It for 550,000

If data is the problem, how do Rosanne and her team solve it? To get "realtime, by name" data, Community Solutions brings together the organizations who come into contact with homeless persons. The police, libraries, shelters, emergency services, non-profits, faith organizations. People experiencing homelessness are not just interacting with housing experts, but rely on many services. For example, a case of domestic violence may lead to a family break-up, that in turn leads to some members of the family ending up homeless. Social and police services are involved with the people at risk of homelessness, but it is often not their job to consider housing. Together, these organizations maintain an up-to-date list of everyone who is experiencing homelessness, asking their permission to record their personal details. With this new approach, city leaders don't just get a generic number, but what specific situation the person is in. As a team, they can then determine the specific support needed to get this person out of homelessness.

Ninety-eight cities have joined Built for Zero, sixty to have "realtime, by name" data, and fourteen have achieved functional zero homelessness.

Does it work? In the US today, ninety-eight cities have joined Built for Zero. Of these, sixty-two have achieved quality real-time data. Of these, forty-three cities reduced homelessness. Fourteen communities achieved functional zero, for example the cities of Abilene in Texas and Lancaster City in Pennsylvania, which means that they have ended chronic homelessness (people experiencing homelessness for more than a year). Together, they have housed 139,000 people. In 2020, Community Solutions won a one hundred-million-dollar grant from the philanthropic MacArthur Foundation, to help another 75 communities reach functional zero by 2026.

Built Not For, But With 58,000

Brownsville is a neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City. It has a reputation for being among the toughest places to live. It is also an urban planner's nightmare: Brownsville has too much public housing, leaving room for little else. It also suffers from poorer quality public services than other parts of New York City.

In 2008, Rosanne wondered if what worked in the Prince George Hotel could be applied to Brownsville, a neighborhood of 58,000 people. At the time, Brownsville had the highest infant mortality rate in New York, the highest high school drop out rate, the highest murder rate and was among the poorest neighborhoods in the city. The New York City government seemed to have overlooked the neighborhood for decades and was slow to act.

The only way to apply the lessons of the Prince George to Brownsville, a neighborhood of 58,000, was to involve its people, put them in charge.

Rosanne’s vision was for Brownsville to become a stable neighborhood, safe and supportive for people to build better lives. Like with the Prince George, it would have to include not just better housing, but better public services. But where to start in a neighborhood with so many problems, so much violence, so much neglect? Brownsville is different from the Prince George in important ways. Unlike a building with tenants, it is a neighborhood, with no contracts or gates. And working with 58,000 people going about their lives is a different ballgame from working with 416 people who live in supported housing. And unlike the Prince George, the hundreds of services the community receives, from schools to health, welfare to street cleaning, housing to policing come from different New York City agencies. Brownsville is alive. In her mind, the way to get involved with Brownsville is to involve its people, to put them in charge.

Seeding Empowerment

Community Solutions got the ball rolling by founding The Brownsville Partnership. They started out by hiring residents with deep connections in the community to become community organizers, and had them trained by world-class experts at Harvard University. It was critical to hire locally, to develop the skills and the muscle for the Brownsville Partnership to be led and run by the people of Brownsville. Community organizing is much more than a meeting. It is a process of listening, building trust, learning, ideation and holding partners accountable. Done well, the residents of Brownsville would become knowledgeable and empowered to shape their destiny and hold New York City agencies accountable.

A critical milestone for the community was to have a vision, and actual plan where they wanted to go. In 2017, nine years after the process started, they published the Brownsville Plan, and submitted it to the city. Until then, in their 160-year history, Brownsville residents had never expressed their ideas for the future. In fact, it was expert city planners who inflicted the greatest harm on the neighborhood in the 1970s, when they designed great schemes for Brownsville, instead of with Brownsville. This kind of community organizing was new to Rosanne’s work. It took a long time, several years, but she saw it as a critical foundation to build on.

Reimagining Early Childhood

The Brownsville Plan was about re-imagining Brownsville. One of the priorities, raised by families, was to change what it is like to grow up in Brownsville, especially the early childhood experience. People wanted a healthier, more supportive and safer environment for children and families. Local people and services providers came together with experts to create United for Brownsville in 2018. Funded by Robin Hood, a non-profit that fights poverty, United for Brownsville is a partnership between Rosanne's organization, Community Solutions, and SCO, a large non-profit that provides family services. Their goal is to improve early childhood development, especially the social-emotional learning and language skills of 0-3 year old kids. Their goal: to set children up for equal opportunities in education and life.

I spoke to Kassa Belay and David Harrington, the co-directors of what is called the ‘backbone’ of United for Brownsville. The backbone team facilitates the collaborations among families and service providers. United for Brownsville is unusual in that it is led by both parents and service providers. Twenty-one local family members constitute the Family Advisory Board. In Kassa and David's eyes, their lived experiences make them experts, and United for Brownsville pays them for their expertise. More than forty providers of social, education, and health services for infants and toddlers constitute the Provider Action Team. United for Brownsville chose this setup to address the racial inequities that marked city services in Brownsville.

In Rosanne's mind, what connects all pieces of the journey is a passion for putting data to use. Not in a technological sense, but as an organizing principle.

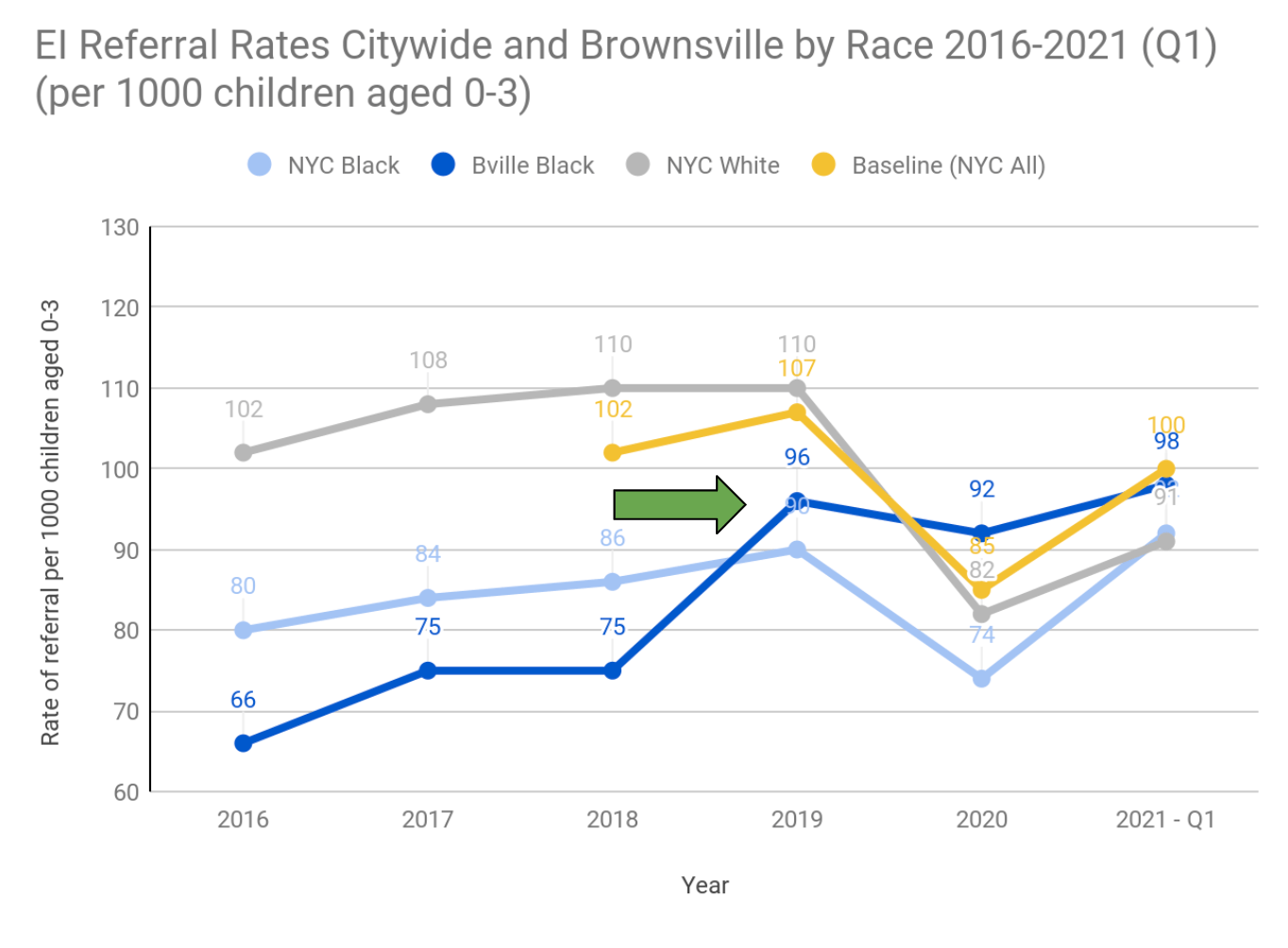

Early Intervention is one such service. It is a free service offered by the city to children 0-36 months old who have developmental delays. Parents of Black and Hispanic Children in Brownsville were using this service at much lower rates (-30%) than in other parts of the city. The Family Advisory Board investigated and reached back into their communities. What they found were several barriers families experienced in using Early Intervention services. They found that people were afraid of the evaluation process, in which an expert usually visits the home of a child to diagnose them for developmental delays. Families were afraid of these visits, found them intrusive, and felt like their home life would be inspected. To overcome this fear, United for Brownsville created a new idea. Families created a new role at United for Brownsville, the Early Intervention Ambassador, who would help families navigate the Early Intervention system and provide neutral space for meetings. The Family Advisory Board led the recruitment, selecting Danny Herring, an experienced special needs educator also from Brooklyn and herself the mother of a child with special needs.

Everyone Works the Data

Kassa and David point out the transformative role of quality data in the work of United for Brownsville. More than a decade ago, people like Rosanne sensed that New York City public services performed more poorly in Brownsville. For years, city agencies dragged their feet to share information with United for Brownsville. But Early Intervention was willing to share data. It showed inequities and lead to specific conversations about people, their needs, and what needed to be done to support them. By relying on families as intermediaries, United for Brownsville could reach out to other families in the neighborhood. In a place where people don't trust people in power, this proved critical. Just as it had for User Voice, in a London Prison (see Story #1). Ten years of cultivating trust, and developing capabilities in Brownsville now paid off exponentially when it came to working with this data. Families put the referral data to good use. By 2021, referrals of Black and Hispanic children were practically on par with the rest of the city, with uptake now higher than in any other New York City borough.

Betting on Brownsville started out as a hypothesis, an experiment to let a community take charge. For Rosanne, it was quite different from the Prince George and Built for Zero programs, in which her organization had provided the vision and led the charge. In Brownsville, it is now families who determine what success will look like. Community Solutions provided patient capital and suppler to let things start slow, nurturing trust, confidence, and capabilities. Things are falling into place for families working with United for Brownsville. They have gained experiences, and new capabilities, by implementing smaller projects for the first three years. Now, empowered by meaningful data, they appear to have the foot firmly on the accelerator.

From Deep to Wide, to Deep-Wide

Rosanne's mission began by witnessing the ineffectiveness of a homeless shelter in New York City. Over the course of forty years, she kept being of service with a relentless focus on progress. Her story reveals three big transitions, in which she went from working deep by building hosing units, to going wide by running national campaigns to end homelessness. In Brownsville, her organization helped bring her insights from going deep and wide together. First, it had to slow down, years went by until the community had found its footing. Then things picked up, as families began to put their capabilities and power to use. In her mind, what connects all pieces of the journey is a passion for putting data to use. Not in a technological sense, but as an organizing principle. Unless cities know their homeless, they cannot end homelessness. And with data, families of Brownsville, officials and professionals can find creative ways that work to transform the neighborhood. At the speed of trust.